Posted by Tim Bray

Most Android apps have some sort of server-side back end, to persist and share data. Even the most basic game needs to remember its players’ high scores. When you’re building your back end, one problem you have to solve is how the back-end code knows what app it’s talking to and who the person using it is.

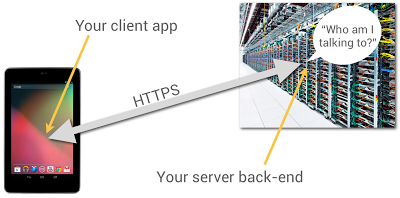

You probably have HTTP endpoints for communicating with your client apps, but how can the server-side code be sure who’s sending messages to it? After all, anyone can send HTTP POST requests from anywhere; could they impersonate your users if they could guess their identities?

It’s really user-unfriendly to ask people to type in usernames and passwords on mobile devices. In particular, if someone has installed your app and given it permission to use the Internet and know your identity, they shouldn’t be pestered any more.

It turns out that Google Play services, now available on every compatible device running Android release 2.2 or higher, offers a good solution to this problem, based on the use of Google Accounts.

Summary

Doing this is a multi-step process, which I’ll outline in full, but here’s the short version: You use the GoogleAuthUtil class, available through Google Play services, to retrieve a string called an “ID Token”. You send the token to your back end and your back end can use it to quickly and cheaply verify which app sent it and who was using the app.

This capability is built into Google facilities such as App Engine’s new Cloud Endpoints feature, which bakes app/back-end identity into a simple programming model.

Now let’s get to the details.App Registration

You’re going to have to use the Google API Console quite a bit in this process. You’ll need to make a new project for this purpose; while you can give it a nice human-readable name and graphical branding, it turns out that those resources aren’t used in this particular scenario.

You can also authorize this project to access a large number of different Google APIs; but once again, you don’t need to in this scenario.

You should give serious thought to the people you authorize as members of the project, since these are important administrative roles.

Make Client IDs

You’ll need to make two different OAuth 2.0 “Client IDs” for your project. The first one is a “Client ID for Web applications”. Once again, you can ignore all the labeling and branding stuff, you’ll just need the Client-ID string, which will look something like 9414861317621.apps.googleusercontent.com.

Now you’ll need to make another Client ID for your Android app. To do this, you’ll need to provide two pieces of information: your app’s package name and cert signature. The package name is just the Java-style reverse-DNS, as given in the top-level “package” attribute in your AndroidManifest.xml, for example com.example.identity.

To get your app’s cert signature, use the following shell command:

$ keytool -exportcert -alias <your-key-name> -keystore <your-key-store-file> -v -list

Copy the octets labeled “SHA1”, paste them into the Developer Console field, and create your app’s Client ID. Once again, all you’ll really need from the readout is the Client-ID string.

In Your Android App

You’ll need to call the Google Play services GoogleAuthUtil class to get an ID token; the procedure is as described in Obtaining an Access Token. There’s one extra bit of magic: the value of the scope argument to the getToken(email, scope) method. It has to be the string audience:server:client_id:X, where X is the Client ID of for the Web app, as described above. If our Client ID were the example value given above, the value of the scope argument would be audience:server:client_id:9414861317621.apps.googleusercontent.com.

Magic Happens

Normally, when you ask for an OAuth token, the person using the device sees a challenge, asking them if it’s OK to use their identity to get at some resource or other. But in this case, the system looks at the server-side Client ID in your scope argument, notices that it’s in the same project as your Android app, and gives you the token without pestering the user; they’ve already agreed to a relationship with you, the developer who controls that project.

Send the Token

When you’re ready to start talking to your server back end, you need to send the token string to it. The best way to do this is in the body of an POST message; you could put it in a URL parameter, but they’re often logged. You absolutely must use an HTTPS connection, to keep any men-in-the-middle from peeking at your token.

There’s no particular reason for extra round-trips; if you’re sending a game high score to your back end, just stick the ID Token string in as an extra argument.

Use the Token

When your server receives the token from your Android app, it’s really important that you verify it. This requires two steps:

- Verify that it’s really signed by Google.

- Verify that it’s really meant for you.

Verify Signature

It turns out that this is signed using a Google public/private key pair, and Google publishes the public keys (which we change regularly) at www.googleapis.com/oauth2/v1/certs; go ahead and have a look.

You have to verify that the ID Token, which is actually a JSON Web Token, was signed with one of those certs. Fortunately, there are decent libraries around to do this; in this post, I’ll give pointers for Java, Ruby, and PHP.

The libraries can cache the Google certs and only refresh them when required, so the verification is (almost always) a fast static call.

Verify Token Fields

It turns out that the ID Token has a JSON payload, and most libraries that validate the signatures also give it to you as a hash or dictionary or whatever. Thus, you can retrieve named fields, such as aud and azp and email.

First, you have to look at the field named aud and verify that it’s identical to your Client ID, the string you included in the Android app’s scope argument. Seriously, do not omit this step; if you don't verify the ID Token, then any other developer can spoof requests to your service.

Optionally, you can look at the field named azp (stands for “authorized party”) and verify that it is identical to the Client ID of your Android app. By the way, you can have multiple different Android client apps, each with its own Client ID, in that top-level project.

Let’s assume you’ve done all three of these things. Then, you know that:

- The token was issued by Google.

- The token was sent to a device that was being operated by the person identified in the payload's

emailfield.

You also have high confidence that:

- The token was obtained by the Android app identified by the Client ID in the payload’s

azpfield.

The Client ID only has “high confidence” because non-compatible or rooted Android devices may be able to tamper with that information. But they won't be able to fake the Google signature or the authentication of the device user to Google.

What’s Next?

That’s up to you. You know which person and app you’re talking to, it’s up to you what to do with that information.

Code Fragments

Here’s a Java class that implements an ID-Token checker using the Google Java libraries:

import java.io.IOException;

import java.security.GeneralSecurityException;

import com.google.api.client.googleapis.auth.oauth2.GoogleIdToken;

import com.google.api.client.googleapis.auth.oauth2.GoogleIdTokenVerifier;

import com.google.api.client.http.javanet.NetHttpTransport;

import com.google.api.client.json.JsonFactory;

import com.google.api.client.json.gson.GsonFactory;

public class Checker {

private final ListmClientIDs;

private final String mAudience;

private final GoogleIdTokenVerifier mVerifier;

private final JsonFactory mJFactory;

private String mProblem = "Verification failed. (Time-out?)";

public Checker(String[] clientIDs, String audience) {

mClientIDs = Arrays.asList(clientIDs);

mAudience = audience;

NetHttpTransport transport = new NetHttpTransport();

mJFactory = new GsonFactory();

mVerifier = new GoogleIdTokenVerifier(transport, mJFactory);

}

public GoogleIdToken.Payload check(String tokenString) {

GoogleIdToken.Payload payload = null;

try {

GoogleIdToken token = GoogleIdToken.parse(mJFactory, tokenString);

if (mVerifier.verify(token)) {

GoogleIdToken.Payload tempPayload = token.getPayload();

if (!tempPayload.getAudience().equals(mAudience))

mProblem = "Audience mismatch";

else if (!mClientIDs.contains(tempPayload.getIssuee()))

mProblem = "Client ID mismatch";

else

payload = tempPayload;

}

} catch (GeneralSecurityException e) {

mProblem = "Security issue: " + e.getLocalizedMessage();

} catch (IOException e) {

mProblem = "Network problem: " + e.getLocalizedMessage();

}

return payload;

}

public String problem() {

return mProblem;

}

}

If you wanted to do this in Ruby, you’d want to install the google-id-token Ruby gem, and do something like this:

require 'google-id-token'

validator = GoogleIDToken::Validator.new

jwt = validator.check(token, required_audience, required_client_id)

if jwt

email = jwt['email']

else

report "Cannot validate: #{validator.problem}"

end

For PHP programmers, check out the Google APIs Client Library for PHP, in particular the function verifyIdToken in apiOAuth2.php.